Wendell Berry, Hagia Sophia, & Deathworks

by Erin Doom

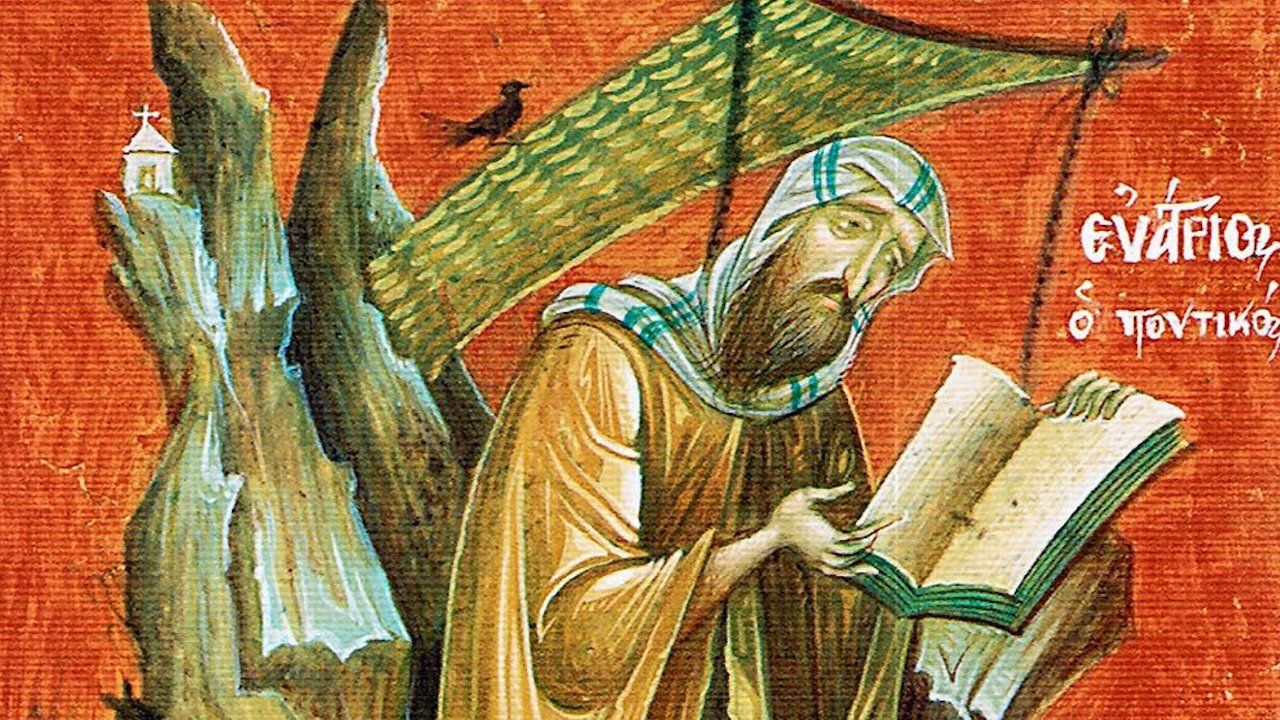

Feast of Our Holy Father Myronus the Wonderworker, Bishop of Crete

Anno Domini 2020, August 8

So if Celsus were to ask us how we think we know God, and how we shall be saved by Him, we would answer that the Word of God who enters into those who seek Him, or who accept Him when He appears, is the one who can make known and reveal the Father. Before the appearance of the Word no man saw the Father. For who else is able to save the soul of man and conduct it to the God of all things except God the Word, who “was in the beginning with God” (Jn. 1:1)? He became flesh for the sake of those who had clung to the flesh, and had become as flesh, so that those who could not see Him as the Word, with God, God Himself, might be enabled to receive Him. And so He spoke in bodily form and announced Himself as flesh in order to call to Himself those who are flesh. He did this in the first place to effect their transformation according to the Word that was made flesh, and secondly, to lead them on high so that they can see Him as He was before He become flesh.

Come, let us rejoice, mounting up from the earth to the highest contemplation of the virtues: let us be transformed this day into a better state and direct our minds to heavenly things, being shaped anew in piety according to the form of Christ (Philippians 3:10). For in His mercy the Savior of our souls has transfigured man and made him shine with light upon Mount Tabor.

O let us who love to see and hear things past understanding, mystically behold Christ shine as lightning with the rays of divine splendor; and let us make the Father’s voice resound, who proclaimed Him as His well-beloved Son (Mt. 17:5). On Mount Tabor he makes bright the weakness of man and bestows enlightenment upon our souls.

Let the assembly of all on earth and in the world above be moved to praise Christ our God, Lord both of the living and the dead (Rom. 14:9). For when He was divinely transfigured on Tabor, the Savior of our souls was pleased to have at His side the leaders and the preachers of both the Law and Grace.

The shining cloud of the Transfiguration has taken the place of the darkness of the Law. Moses and Elijah were counted worthy of this glory brighter than light and, taken up within it, they said unto God: “Thou art our God, the King of the ages.”

The only escape from oppressive impersonal systems is personal knowledge, including personal knowledge of embodied community, of place. “It is not out of the abstract ministrations of priests and teachers from outside the immediate life of a place that the ceremonies of atonement with the creation arise, but out of the thousand small acts repeated year after year and generation after generation, by which men relate to their soil.” For Berry, the mode of healing is incarnational, communal, even liturgical.

There are lessons here for today’s race-awareness advocates, as well as for their critics. Berry insists that racism is a serious problem, and that it must be discussed; but the abstract ministrations of pundits, sensitivity trainers, and fragility consultants, no matter how well-intentioned, often fail because, coming from outside, they do not participate in the ongoing life of a particular place. The healing steps Berry advocates can’t be captured in a campaign or a tweet, much less in a human-resources certification module.

This may explain the irony that a modern classic of American reflection on racism, which specifically calls for honest discussion, barely registers in mainstream discourse of race, neither in the literature of anti-racism and whiteness, nor in attempts to critique such literature on ideological grounds. The Hidden Wound is a reproach to those who don’t take the persistent pain of racism seriously; but it is also an implicit indictment of a corporate industry of “anti-racist” programming.

It seems to me that if one thing is going to knock a person off his or her path, romantic love is maybe the most understandable transgression—love can hobble you, knock you down, get you. If you mean falling in love, yes, that will “get you” if you let it. It’s a fine, powerful experience and we all should have the knowledge of being got by it. But it’s blind, too, as you say. It’s “romantic,” simple and temporary, and it can be destructive. When love comes round, it doesn’t always come and stay with the purpose of making you happy. As I see it, when we marry we give up romance by submitting love to the limits of mortality. The traditional vows seize love by the scruff of the neck and set it down in real life, in the real world. Marriage in the traditional sense is also an economic connection, making a household. Around here people would say in one breath, “We got married and set up housekeeping.” I’m glad I stayed here. I’m glad that I stuck with Tanya. It’s a good thing. But you have to wait, and the necessity of patience invokes a tradition and discipline and way of thinking.

You’re being fed in an essential way by the beauty of things you read and hear and look at. A well-made sentence, I think, is a thing of beauty. But then, a well-farmed farm also can feed a need for beauty. In my short story “The Art of Loading Brush,” when Andy Catlett and his brother go to a neighbor’s farm, there’s a wagonload of junk, and it’s beautifully loaded. Andy’s brother says, “He couldn’t make an ugly job of work to save his life.” In the epigraph I use from Aldo Leopold he questions if there’s any real distinction between esthetics and economics.

The thing that worries me very much is how much language we’re using now that is so abstract as to require no thought at all. I mean very important words. Justice, for instance. I had a list, I think, of eleven kinds of justice. Restorative justice, climate justice, economic justice, social justice, and so on. The historian John Lukacs, whose work I greatly respect, said that “the indiscriminate pursuit of justice . . . may lay the world to waste.” And he invoked modern war, which kills indiscriminately for the sake of some “justice.” He thought the pursuit of truth, small “t,” much safer. I want to remember—and this comes to me from my dad, to some extent—that our system of justice requires a finding of truth, and it labors to see that justice is never done by one person. There’s a jury of twelve. There are two lawyers, at least, and a judge. It doesn’t always work perfectly. Sometimes the result is injustice. But, the effort to discover the truth that goes ahead of judgment is extremely important. It requires us to think about the process and what’s involved.

The idea of conversation seems important to you.

It’s either that or kill each other.

We do that, too.

We do. But it’s a shorthand, a short cut. We are always faced with a choice between solving our problems by communing with one another and with our places in the world—that is, paying respectful attention and responding respectfully—or solving them by applications of raw industrial power: more machines, more explosives, more poison. So far we have been choosing raw power, whether we’re dealing with international “competitors,” or with the land, water, and air of our country. We seem to regard forms of violence as “efficient” substitutes for the respectful, patient back-and-forth that real solutions require. By real solutions what I mean are solutions that are not destructive, that are kind to the world and our fellow creatures, including our fellow humans. Our dominant practice now is to solve problems with other problems. This is now obvious in industrial agriculture. What we need to do is submit, for example, to the influence of actually talking to your enemy. Loving your enemy.

That’s a hard thing to do.

We keep coming to that, don’t we? If we come to these places where we say, “This is hard,” that means that we have got to get back to the details of the work. That’s it. You don’t have to stop in despair.

I attended church under protest. I disliked enclosure, and as I came to consciousness I objected to the belittlement of earthly life I heard too often—but not from my parents. I heard the King James Version quoted and read, and I’m still attached to it. To me, it’s not just an influence on English, some of that is English. What Ruth says to Naomi? And Luke’s passage about the birth of Jesus, and John’s account of Mary’s visit to the tomb—my goodness, that’s my language.

I tried to get along without it, because I thought I was going to be a modern person. But you can’t think about the issues we’re talking about without finally having to talk about mystery. You’ll finally have to talk about the commitment that doesn’t see any end. That’s a life that you are not going to be able to prescribe, that finally you’re not in charge of. I think my dad was speaking religiously when he said, “I’ve had a wonderful life and I’ve had nothing to do with it.” That was a submission. It’s an important word and well, for instance, if you’re not going to submit to the labor of justice, there’s no use in going around talking about distributive justice.

All cards face up and I will push them to the center of the table: I am an Orthodox Christian. I am white from a southern heritage. And I love Batman (the Christopher Nolan one). What do these three have in common? They represent a way of life that is valued for its good. They are also reflective of a type of moral place in society that battles for truth and justice.

What makes these ideals difficult, even diabolical, depends upon the viewpoint and the lens through which these cultures and beliefs are experienced. If you are an Orthodox Christian, you will likely view Hagia Sophia differently than if you are Muslim. If you are a white Southerner, you will likely view a Confederate statue differently than if you are an African-American. This emotional dichotomy drives—even torments—the character of Bruce Wayne between what he is (the heir of a corrupt politician who favors the rich) and the person he wants to be (a legend of truth and justice).

With this step it’s being said to the world that “Even though we live in the 21st century, our mentality is still that of 1453. Even now, in the 21st century, we are utterly unconcerned with preserving the cultural heritage of humanity. Among us, there’s no sense of a greater cultural inheritance beyond that which was left to us; we have nothing to contribute to humanity’s cultural treasures. We are unable to create any new cultural value ourselves. We seize the cultural treasures of humanity, we break them and/or we destroy them.”

This is what’s being done. Here, now, in the 21st century, the Hagia Sophia, one of the most significant monuments of human culture will again be “conquered” and turned into a mosque, just like in 1453.

What’s being performed here is an act of cultural vandalism.

Philip Rieff (1922-2006) stands as one of the 20th century’s keenest intellectuals and cultural commentators. Rieff did sociology on a grand scale—sociology as prophecy—diagnosing the ills of Western society and offering a prognosis and prescription for the future. Although he was not a Christian, his work remains a great gift—even if a complicated and challenging one—to Christians living in a secular age.

In his work, the Western church will find a perceptive diagnosis of Western society and culture and an illuminating, though insufficient, prognosis and prescription.

Rieff argued that Freud’s exploration of neurosis was really an exploration of authority, as Western man was coming to view the notion of divine authority as an illusion. If God does not exist, appeals to divine authority are illegitimate. Freud recognized that as belief in God was fading, psychological neuroses were multiplying. He posited a cause-and-effect relationship between the two phenomena but, instead of healing neurosis by pointing persons back to God, Freud sought to heal it by teaching his patients to accept this loss of authority as a positive development.

This psychotherapeutic view of modern man came to serve as a unified theory of modern society. In Rieff’s view, therapeutic ideology, rather than Communism, was the real revolution of the twentieth century. Compared to Freud, the neo-Marxists were cultural conservatives who still believed in the notion of authority and the idea of a cultural code. The proponents of Freudian therapeutics, on the other hand, would not countenance authoritative frameworks and normative moral codes. In a therapeutic culture, authority disappears. In place of theology and ethics, we are left with aesthetics and the social sciences. Thus, therapeutic culture was born. This tradeoff would turn out to be so destructive that Rieff would describe the United States and Western Europe (rather than the Soviet Union) as the epicenter of Western cultural deformation.

Deathworks is a devastating critique of modern culture, focusing on our vain Western attempts to reorganize society without a sacred center. According to Rieff, a patently irreligious view of society—which many Westerners desire—is not only foolish and destructive, but impossible. We can no more live without a religious framework than we can communicate without a linguistic framework or breathe without a pulmonary framework. Religion is in our blood, and the more we deny it, the sicker our society becomes. As Rieff surveyed the 21st-century Western world, he perceived the sickness had become nearly fatal.

“St. Benedict called that kind of person a gyrovague,” I told the Pastor. “He said they are the worst kind of monk, because they have no stillness. They just take and take and take, and never grow spiritually. They are ruled by their desires and passions.”

The problem we have with the Christian churches in America is that we are a nation of gyrovagues. We live in a secular culture that holds up gyrovaguery as a normative way of life. The churches cater to that. No wonder nobody takes us seriously, least of all our own people. We think we’re pilgrims, but in truth, we’re nothing but tourists. The pilgrims seeks to find; the tourist is in love with the novelty of seeking.

We are witnessing the dismantling of American liberal democracy, and the conditions under which it thrives. It is an emergency, but relatively few people are treating it like an emergency.

This is the basis for the coming American version of China’s social credit system. Notice that none of this has to do with the government. If you think totalitarianism is only something that the state can impose, you’re wrong. This is what Woke Capitalism is doing to us. We are in a different world now.

I’m telling you, this new order is already largely in place, and we are passively accepting it. We are being conditioned to accept it. I am absolutely not saying that we should surrender to it—in fact, quite the contrary. What I’m saying is that it is no surprise that the American people have been demoralized and manipulated. The “silent majority” is not going to save us, because if it even exists, it is likely already neutralized, or soon will be—and might never understand why or how. We should be standing behind political leaders who recognize the threat from this data grabbing, and who are prepared to fight it, and fight it hard. (Donald Trump is not that leader; Sen. Josh Hawley and Sen. Mike Lee might be.) But in the meantime, we should be preparing ourselves for the long resistance. Totalitarianism is coming. It will be softer than what existed in the Soviet bloc, but totalitarianism it certainly will be.

We have been living, he said, in a condition “like the eight minutes twenty seconds between when the sun dies and we experience it.” He’s talking about the time it takes for light from the sun to reach earth. If the sun suddenly went out, it would take eight minutes and twenty seconds for people on earth to realize it, because that’s how long it will take for the sun’s final rays to arrive here.

That 8:20 metaphor has been sticking with me since my conversation with Mr. Smith over the weekend. An alternative title for The Benedict Option would be The 8:20 Project, given that the point of that book is that we are facing the collapse of Christianity, and that Christians should use the time we have now to prepare themselves, their families, and their communities for a situation unlike that seen in the West since the collapse of the Roman Empire. No, the Church itself did not collapse when the Roman state and economic apparatus did; my point is that there was a dramatic collapse of a civilizational ethos and system.

We are living in the 8:20. We are a post-Christian civilization, but most people haven’t yet realized it. Those who do must busy themselves making preparations for keeping the light alive through the long night ahead. I’ve mentioned here before, and mentioned over the weekend in conversation with Mr. Smith, the story I heard from a German Catholic I met in Rome. This man told me that he and his Catholic friends have accepted that at some point in their lifetime, and certainly in the lifetime of their children, the institutional Catholic Church is going to collapse in Germany. They are busy now thinking of ways to keep the faith alive. One thing they can do is to form their children strongly in the faith at home, and to encourage them to marry only other strong Catholics raised in the same way. Endogamy, in other words: marrying within the “tribe.”

In his column, Damon Linker asks: What are the forces that bind us as Americans? Right now, I’m having trouble seeing those as greater than the forces that are tearing us apart. What could turn that around? The deepest reason for my pessimism is that we have become a people who cannot see any good greater than our own desires. This is not a left-wing or a right-wing thing; it’s who we are here in late modernity. It’s the Triumph of the Therapeutic.

What if we are depressed as a nation, and have been for a while? What if 2020 is so freaking awful because the Covid-19 lockdowns have exacerbated our condition? What if one hidden wound in the body politic is sexual frustration—the frustration of those who cannot find connection with others, for whatever reason, and the misery of those who, seeking release, have turned to pornography, and seduced by the lie that it is an adequate substitute for bodily communion with a beloved, have become enslaved by it?

What would it mean for an entire civilization to commit erocide?

What if the militancy of activists, marching on the streets and through the institutions, is really a manifestation of desperate bored fatigue?

What if we want to burn it all down because it’s interesting to see things go up in smoke?

What do we do then?

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.